Timeline of events leading up to police presence

1:59pm: Nakba memorial rally in front of the Physical Sciences Lecture Hall. Students dropped banners from the second floor balcony, which is accessible by an outdoor staircase that leads to the upper sections of the lecture hall.

1:59pm: Nakba memorial rally in front of the Physical Sciences Lecture Hall. Students dropped banners from the second floor balcony, which is accessible by an outdoor staircase that leads to the upper sections of the lecture hall.

(Photo taken by IFA board member)

On Wednesday, May 15, 2024, UCI students called for a protest around the encampment to commemorate the 76 years of the Nakba. At around 2:15pm, the Nakba Commemoration rally assembled outside the Physical Sciences Lecture Hall (PSLH).

2:01pm: Family and community members present to commemorate the Nakba memorial.

2:01pm: Family and community members present to commemorate the Nakba memorial.

(Photo taken by IFA board member)

Around 2:30pm, students dropped banners from the balcony, as they have done during previous rallies. The students inside the encampment opened up the barricades around the camp and arranged the shade structures and tents along the plaza side of the building, what was widely understood as a symbolic gesture. The rally, which included families and small children, continued peacefully, encircling the encampment and the entrance to the PSLH building.

By 2:50pm, the Irvine Police Department began to swarm the parking lot and helicopters (up to six) droned overhead. The first zotALERT, sent at 2:51 pm, labeled the event a “violent protest,” a dangerously inaccurate claim. Shortly thereafter, alarms in all campus classrooms went off, making many believe there was an active shooter on campus.

.

2:55pm: Irvine Police Department arrives in droves donned in riot gear.

2:55pm: Irvine Police Department arrives in droves donned in riot gear.

By 3:15pm, only an hour after the rally began, dozens upon dozens of squad cars arrived, including forces from at least 22 confirmed different police departments (UCI Police Department, Irvine Police Department, the Orange County Sheriff’s Office (which was the subject of a scathing 2021 government report on violent, abusive and illegal behavior against civilians), California Highway Patrol, Costa Mesa PD, Fountain Valley PD, La Palma PD, Tustin PD, Newport Beach PD, San Clemente PD, La Habra PD, Los Alamitos PD, Buena Park PD, Laguna Beach PD, Santa Ana PD, Orange PD, Westminster PD, Placentia PD, Alhambra PD, Huntington Beach PD, Anaheim PD, California State University PD). Neither the Chancellor, the University Administration, UCIPD, nor any of the police agencies involved in clearing the encampment have publicly clarified the rationale used to call each of them to UCI when there was no threat of violence or even large disruption to campus, while officers have provided inconsistent and divergent accounts of what they were told was going on before they arrived.

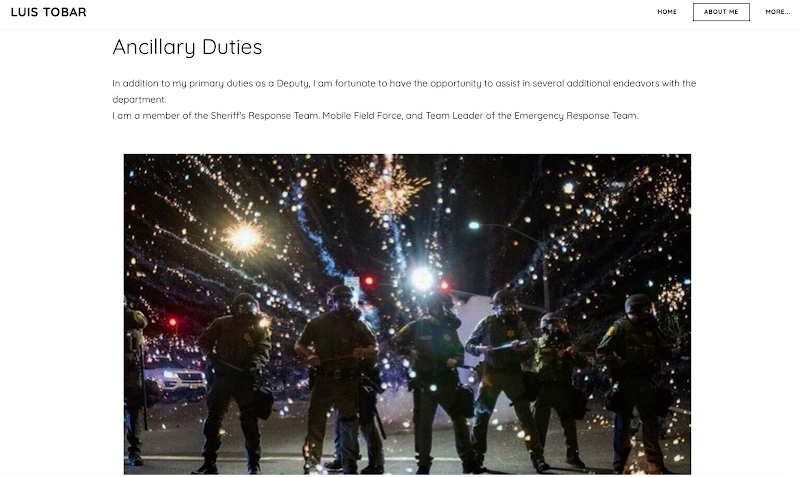

3:21pm: OC Sheriff Deputy Luis Tobar (top left), who kept his hand on his holstered gun, as students and faculty pass by the parking lot to videotape and photograph the massive police response. (Photo taken by IFA board member)

According to Deputy Tobar’s personal website (bottom screenshot), he is assigned to the OC Sheriff’s Intake and Release Center in Santa Ana, CA. His website also has multiple postings of himself completing military-style training drills.

Unlike in previous days, there was no effort by police, private security, or staff from Student Services to talk to faculty liaisons, which included IFA board members, who were present throughout the encampment’s duration to ensure open lines of communication. Instead, they ignored established procedures of de-escalation and other intermediary steps.Police and Sheriff’s forces moved into various formations in the parking lot behind the Interdisciplinary Science and Engineering Building, while police with weapons were posted on top of two surrounding buildings. Soon, however, the police presence far outnumbered the people engaged in the protest.

Around 4:50pm another message by the university administration was sent to the entire campus and shared on social media. It falsely claimed that “several hundred protestors entered the Physical Sciences Lecture Hall on the UC Irvine campus and began surrounding the building.” This was categorically untrue. In reality, a small group of protestors went very briefly inside the PSLH while the rest of the rally continued outside the building. Moreover, there were no other students in the hall at the time, no classes were taking place, and no other students were attempting to enter; the building was entirely empty by the time the police arrived.

The administration only corrected this statement hours later (around 11:00pm), admitting that protesters had not entered the building but merely arranged themselves around it; instead of “several hundred” protesters, this tweet clarified that there were merely “several.” That is, the original tweet had overestimated the number by 100 times. By then police had arrested more than 50 peaceful protestors, most of them students. Media reporting on the event also repeated the misinformation they had received from the Chancellor’s office and administration.

The inability of campus leadership to coordinate or control so many police forces led to confusion and fear in the larger campus community throughout Wednesday evening: for instance, the total communication breakdown led many University Hills residents to be prohibited from entering or leaving their own neighborhood for an extended period, even to go to urgent doctors’ appointments; similar miscommunications occurred in student housing, including in buildings half a mile away from the police action. This is further evidence of how dangerous it is for the campus to bring in this many outside agencies, including those over whom they have no direct jurisdiction, and to fail to follow established guidelines for so doing.

Local police and sheriffs wield batons while one officer points a tear gas launcher at point blank – that is, lethal – range, in direct contravention of City of Irvine “use of force” guidelines. In the background, a peaceful protester is dragged to the ground and arrested.(Photo: Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Local police and sheriffs wield batons while one officer points a tear gas launcher at point blank – that is, lethal – range, in direct contravention of City of Irvine “use of force” guidelines. In the background, a peaceful protester is dragged to the ground and arrested.(Photo: Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

During the police engagement and arrests, dozens and dozens of UCI students, staff, and faculty were beaten with batons, threatened with tear gas and other weapons, and thrown to the ground. A total of nearly 50 students, faculty, staff, and community members were arrested.

Scores of police and sheriffs officers in riot gear and batons out as they descend the staircase to Aldrich Park. (Photo taken and posted by @SMALLANDEFFETE on X (formerly Twitter).

FAQs

Didn’t the campus have to respond to this “escalation,” especially if it involved occupying or blocking a building?

What happened prior to the arrival of hundreds of police was not in fact an “escalation.” No classes were occurring in, or scheduled for, the PSLH building at the time. Whatever “disruption” only began when the administration decided to send misinformation across campus and around the world, following that up with its ill-fated decision to call in hundreds of armed police. It was the administration itself that canceled classes on Wednesday afternoon and moved all class, research, and work online for Thursday.

Ok, so what happened on May 15th, 2024 was not an escalation. But what if campus administration thought it was? Didn’t they have to do something?

First, we should ask whether it was remotely reasonable for the administration to assume that “hundreds” of students were occupying the building, or that protestors were “swarming” the campus. No one who was present would have had even the slightest reason to believe either of these claims. There were not “hundreds” of students in the encampment at any point, and the rally around the building was only approximately one hundred people before the arrival of the police.

Moreover, faculty and staff who had for the previous two and a half weeks been working around-the-clock as liaisons between the encampment and police, security, and Student Affairs and who were present at the rally and trying to prevent police escalation, were NEVER consulted about what was going on. There was NO effort on the part of the administration or those on-site to ascertain what was happening and gather facts before calling in 22 heavily-armed police units. There was NO effort to speak to the students around the building, to understand their plans, to determine what was happening or to warn them that their actions were about to lead to a massive escalation on the part of the administration.

It is crucial to note here that the resulting response clearly violates UC-wide policy made by UCOP in a 2021 “UC Community Safety Plan” created in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests, which specifies that “The University will…minimize police presence at protests, follow de-escalation methods in the event of violence and seek non-urgent mutual aid first from UC campuses before calling outside law enforcement agencies.”

Most broadly: it is worth considering the historical context and meaning of “non-violent” protest. We can look to the long history of building occupations (including on college campuses) as a tactic of non-violent civil disobedience—from the Civil Rights movement, to the anti-war movement, to the Disability Rights movement, to the LGBTQIA struggle, to the fight for climate justice. None other than our own Chancellor Gillman, in his book Free Speech on Campus, co-written with Erwin Chemerinsky, has noted that both authors “grew up in the time of the civil rights movement and anti–Vietnam War protests. We saw first-hand how officials attempted to stifle or punish protestors in the name of defending community values or protecting the public peace. We also saw how free speech assisted the drive for desegregation, the push to end the war, and the efforts of historically marginalized people to challenge convention and express their identities in new ways. In our experience, speech that was sometimes considered offensive, or that made people uncomfortable, was a good and necessary thing.” Gillman and Chemerinsky correctly extend the idea of protected “speech” to acts of protest like sit-ins, boycotts, and attempts to occupy public space, and decry efforts to stifle such speech in the name of “community values.” As Irvine Mayor Farah Kahn put it on Wednesday evening: “Taking space on campus or in a building is not a threat to anyone. UCI leadership must do everything they can to avoid creating a violent scenario here. These are your students w/ zero weapons.”

What about the “outside agitators”? Are they to blame for all this?

The UCIPD made no attempt to determine whether there were “non-affiliates” present inside the building or around it before escalating and calling for mutual aid from 22 other police departments. Furthermore, UCI is a public university, and so the campus is open to the public.

We would also remind our community that the rhetoric of “outside agitators” in the U.S. dates back at least to the John Birch Society and the segregationists, and that it has always been both an anti-Black and anti-Semitic discourse. For this reason alone, we should ALWAYS approach these claims with a great deal of suspicion.

In the case of the UCI encampment, the language of “outside agitators” or “non-affiliates” is even more offensive and problematic. UCI is a public institution and an open campus. Yet Gillman has consistently defined “UCI community” to intentionally exclude the numerous Palestinian, Middle Eastern, Arab and Muslim students, faculty, staff who have attended, worked at, donated to, and supported UCI for decades. His first statement on the encampment, disseminated April 29th, ominously referred to the presence of people “not affiliated with the university.”

Those of us who spent time at the encampment know that concerned mothers, fathers, and grandparents from the community came to visit the encampment simply to share a moment of solidarity at a deeply painful time and to ensure that their students, children, and community members are safe and fed. They were welcomed and offered consistent moral support. These members of the community had seen—some of them first-hand—the two nights of brutality that had occurred at UCLA, a few weeks earlier when the encampment was violently attacked first by counterprotestors, including those from white supremacist organizations, and then by police. The local community was thus committed to making sure the same thing didn’t happen at UCI. They were there to protect the students and the encampment with their bodies. That some of them were willing to subject themselves to arrests and to harassment and violation targeted specifically at female-identified, non-white, and Muslim protestors speaks volumes to their courage and commitment, and the campus should be honored to stand beside them.

What has happened to all the students, staff, and faculty who were arrested?

Nearly 50 people were arrested and mostly charged with misdemeanors. Many sustained injuries. Many arrested students have received a 7-14 day stay-away notice. This means that they are not allowed to be on campus and that they are barred from entering their on-campus dorms and apartments. All arrested students are also currently facing university student conduct charges and have received interim suspension notices: suspended students are unable to go to class in person or access on-campus housing despite still paying rent and tuition; suspended graduate students are still mandated to teach or work remotely despite being banned from classrooms, offices, labs, and housing.

What had happened in the negotiations before May 15th?

Students representing the encampment, along with faculty mediators, entered into negotiations with Chancellor Gillman’s office over their demands soon after the encampment was established. On Monday, May 6th, negotiators notified Chancellor Gillman’s office that his initial letter to the campus community violated the good faith agreements between negotiators and the university, including the basic principle that those involved in a negotiation should not make public statements about ongoing closed-door discussions nor publicly disparage those they are negotiating with. During that meeting, negotiators also requested basic financial and university investment information, which the Chancellor’s office refused to disclose. Student and faculty negotiators notified the Chancellor’s negotiating team that they would return to negotiations after they had a chance to discuss the Chancellor’s proposals with the other students in the encampment. The negotiators verbally agreed to this and stated that they would wait for the students’ response.

The next day, the Chancellor’s office asked to meet again, and the students explained that the proposal was still being reviewed. Chancellor Gillman’s Chief of Staff responded to the faculty member advising the students in their negotiation saying that they looked forward to continuing negotiations. Thirty minutes after this message, Chancellor Gillman himself sent out a letter to the UCI campus community accusing students of being uncooperative and unwilling to meet.

The very next day, multiple UCI students received notifications of interim suspensions from the university—including three students who were part of the negotiation team. Even as students and their faculty mediators assumed they were still involved in good-faith if difficult negotiations, the Chancellor’s office was complaining–incorrectly–that students had left the negotiations and suspended them for so doing. The students were charged with “disorderly conduct,” which directly contradicted Gillman’s previous statement thanking the students for keeping the encampment peaceful and minimally disruptive. In addition to prohibiting students from being physically or virtually present on campus, the suspension stated that “this exclusion from UCI includes any and all University housing facilities.”